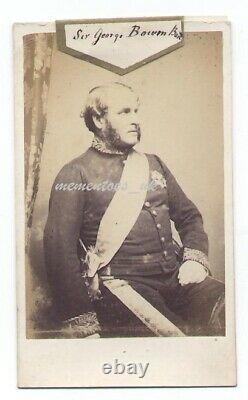

CDV c1868 Hong Kong China Governor Sir George Bowen Australia New Zealand

Rare Albumen Carte de Visite Portrait image of Sir George Bowen Sir George Ferguson Bowen GCMG PC Chinese:?? 2 November 1821 - 21 February 1899, was an Irish author and colonial administrator whose appointments included postings to the Ionian Islands, Queensland, New Zealand, Victoria, Mauritius and Hong Kong Please see bio below. Condition is good for age, complete, please see scans.

All items are professionally packaged in board backed envelopes or padded envelopes, both with extra backing card etc. Inside to ensure safe arrival of your items.

He went to Charterhouse, won a scholarship to Trinity College, Oxford, where he was twice president of the union and took first-class honours in classics B. 1847, and began to read law at Lincoln's Inn. In 1846 he had some naval training, serving for sixteen days in the Victory. In 1847-51 he was rector of the Ionian University at Corfu, and joined the colonial service as political secretary to the government of the Ionian Islands.He travelled widely and wrote several political pamphlets and three books: Ithaca in 1850 (London, 1851); Mt. Athos, Thessaly and Epirus (1852); and a Handbook for Travellers in Greece (1854). In 1856 he married Diamantina, daughter of Count Candiano di Roma, president of the Senate of the Ionian Islands. Bowen had been elected to a fellowship at Brasenose, which he held in 1851-54.

In the 1852 elections he campaigned vigorously for Gladstone, through whose patronage he was appointed in 1859 the first governor of Queensland. On 10 December Bowen was welcomed in Brisbane as a friendly tutor in the enjoyment of the fruits of separation from New South Wales.

His influence was greater than that of the governors in other Australian colonies which already had responsible government, and much of it stemmed from (Sir) Robert Herbert, who accompanied him from England, became colonial secretary and was premier in 1860-66. Because of Bowen's friendship Herbert's influence and ideas were reflected in the legislation they drafted together.Bowen preferred to act through parliamentary institutions, rather than as an autocratic governor. Always willing to hand over responsibility, he appointed ministers and an Executive Council within a week of his arrival, appreciative of the existing administrative departments already established under control from Sydney. Bowen tried to expedite elections for the first Legislative Assembly and regretted their delay until May 1860, but deferred to the judgment of his chosen advisers. The legislation most urgently needed was on land, immigration and education. Bowen exaggerated the success of the Land Acts when he claimed that they had'settled that long quarrel between the pastoral and agricultural interests which has raged in all new countries since the days of Abel the "keeper of sheep" and Cain "the tiller of the ground".

That quarrel continued during and after his governorship; while agriculture had limited success, the fortunes of cotton and sugar fluctuated and other crops expanded slowly but the pastoral industry remained dominant with Bowen's support. Politically he heeded a warning from the Colonial Office to avoid support of either pastoralists or their opponents and to'abstain as much as possible from interference'. Socially, however, his sympathy was with the squatters.

He gave fulsome praise to the gentlemen squatters he met on his extensive tours, especially on the Darling Downs, even writing of the'sublimity' of the pastoral expansion. He enjoyed riding, shooting and fishing with them and recommended that no governor lacking these outdoor skills should ever be sent to Queensland.

He also pleased urban interests by his ready accessibility and by the generous hospitality he and his wife displayed in Brisbane and the other small towns. Bowen supported immigration, realizing that'the most pressing need of Queensland is an accession of population to develop the rich and varied resources and capabilities of our vast territory'; yet the 1860 land order system neither worked well nor attracted sufficient farmers and had to be amended in 1864.

Bowen hoped to attract Indian labourers to supplement other workers'in the tropical districts where the climate (though salubrious) is too hot for Europeans to work in the fields'. When his ideas were opposed, his arguments revealed some of his prejudices:'if capitalists and colonizing companies are not permitted to introduce Indian labor under proper regulation and supervision, they will ere long deluge North Australia with Chinese, Malays, Polynesians and hordes of other labourers under no regulation or supervision whatsoever'.

His plan for Indians and later for Maltese immigrants failed. He then suggested Chinese immigrants, hoping they would prove'industrious labourers on cotton and sugar plantations', but few of those who arrived worked on the plantations to which Pacific islanders (Kanakas) were introduced in spite of government policy. Always a good'trumpeter' for Queensland, Bowen visualized even before he arrived an expansion of population and production with towns set on'a chain of capacious Harbours at successive intervals along the coast'. The new settlements of Port Denison, Cardwell, Burketown and Townsville owed much to his enthusiasm. He gave special attention to investigating and encouraging a settlement on Cape York for which he held grandiose hopes as a future Australian Singapore.

The resultant undeveloped settlement at Somerset typified his failure to impress the British government with the importance of either his ideas or Queensland's potential. Bowen's interest in education was reflected in his speeches, for example, his spirited defence of classical education and competitive examinations.

In 1860 he introduced entry tests for clerks joining the Queensland public service. He welcomed the government's support of local efforts in founding primary and secondary schools, wanting the latter to fulfil the role of the English public schools and the Irish Queen's colleges. He praised the encouragement of tertiary education by government scholarships to Australian and especially British universities, and hoped they would'strengthen the cordial relations existing between this Colony and the Mother Country'. He regretted the government's decision to end payments'on account of public worship', preferring to see'the system of "State Aid" continued on a more liberal scale. Until Churches should have been built and Public Worship firmly established not in the towns only, but also throughout the pastoral districts of the colony'.

Although Bowen supported the increase of government as against church schools he tried to steer clear of sectarian issues. He avoided rather naively the conflicting claims to precedency between the heads of the Churches of England and Rome by'taking care that the rival dignatories are never asked to dinner at Government House on the same day'. But he was soon drawn into disputes, sensationally when Bishop James Quinn threatened him with'dreadful consequences' if he did not support Roman Catholic views; later rumour had Bowen about to be replaced by a Roman Catholic governor, possibly Sir Dominick Daly.Bowen also faced criticism from radicals centred around Judge Alfred Lutwyche. He survived their constant attacks in 1859-64 and managed to remain fairly aloof but in 1863 he reported to the Colonial Office:'probably there is no precedent in England for an onslaught of this nature on the Ministry and Parliament of the day by a criminal and common law judge, in the midst of the excitement of a general election. Lutwyche's conduct equally deplorable if he had issued his manifesto in favour of, instead of against, the political party now in office'. In 1866 Bowen faced his most violent criticism, culminating in petitions for his removal on the grounds that he had overstepped the limits of responsible government. Bowen tried to persuade his ministers against the bill, arguing against repetition of the error of assignats in the French revolution and of greenbacks in the United States.

When Bell, backed by the premier, Arthur Macalister, introduced the bill, Bowen reserved it and refused to yield. When Macalister resigned, Bowen recalled Herbert for a brief ministry. Meanwhile Bowen had been reviled by his executive, attacked in parliament, press and public meetings and faced with petitions for his recall. His advice to his ministers and his reservation were later upheld by the Colonial Office, especially as his Instructions specifically required him to reserve any bill making paper legal tender. As Macalister was defeated in parliament in May and August 1867 it can also be argued that Bowen did not oppose majority legislative opinion, although he probably exceeded his powers in appointing Herbert.

The crisis at this stage in the evolution of responsible government in Queensland showed that a strong governor, convinced of the lack of wisdom in the course of action chosen by his responsible advisers, could find a reason for intervention and survive opposition and subsequent constitutional irregularities. The incident needs to be compared with Bowen's experience in Victoria in 1878. Bowen's views were those of an English Liberal-Conservative and he showed clear opposition in Queensland to what he called the extremes of ultra-democracy and autocracy. The extent of his influence suggests the degree of opposition in Queensland to democratic and radical ideas.At the same time his refusal to become committed to any local interest, particularly to the squatters, encouraged the development of political factions. In 1868 Bowen succeeded Sir George Grey in New Zealand. His dispatches continued to be long and flowery but W.

He was in the colony at the end of the Maori war and boasted of his visits to Maoris,'helping to confirm the loyalty of the well-affected, and of winning back to allegiance such of the tribes as had revolted against the Queen's authority'. In March 1873 Bowen took office as governor of Victoria, where he faced a political crisis reminiscent of 1866 in Queensland. It began during his first leave, which he spent in England from January 1875 to January 1876, when the acting governor, Sir William Stawell, showed'too little flexibility in the exercise of his temporary powers'. Bowen was well aware of the increasing rivalry and in October 1877 told the Earl of Carnarvon that'a sort of political madness has seized on both sides, and that language rarely heard in British communities is openly held; some members of the Council talking of hiring and arming Irish mobs, forming vigilante committees, etc. While some members of the Assembly advocate violent and revolutionary measures'. Bowen was strongly opposed to the council's tactics and argued with its president, Sir William Fancourt Mitchell and the support given by the conservative Argus. Anticipating a deadlock between the Houses Bowen, for his first time as a governor, sought guidance from the Colonial Office. Herbert told him to follow his ministers' advice in virtually all circumstances, specifically on spending moneys approved only by the assembly, although he regretted that'the power of self-misgovernment conceded to the Australian Colonies has hardly any conceivable limitation so far as intra-colonial questions are concerned'. Backed by Herbert's advice, Bowen thought he was safe in consenting to Berry's attempt, aimed at some of the council's major supporters, to break the deadlock by a wholesale dismissal of public servants on the so-called'Black Wednesday'. Private and confidential letters from Bowen to Berry one of them marked'do not mention this to any one. Burn this letter' reveal the close alliance between governor and premier.Bowen was advising Berry throughout, for example, suggesting what to include in the address to the Queen and tell the Age but not other newspapers and rebuking him for speaking too much in the past to the press. Berry was opposed at first to the sweeping dismissals but his hesitations had been overcome by his colleagues.

Bowen did not stand in the way but later persuaded Berry to reinstate a few officers. The governor probably exaggerated when he later claimed to have'saved the Banks, the currency and the trade of Melbourne from molestation and danger at the hands of certain extreme parties'.Bowen realized in May 1878 that'my reluctant consent, purely on constitutional grounds, to these dismissals. Has damaged my further reputation and my career to a degree that I shall never recover. It will never be forgotten either in England or in the Colony'. Bowen was unlucky when Sir Michael Hicks-Beach, who had replaced Carnarvon, disapproved Herbert's advice and virtually recalled Bowen in August 1878. The governor undoubtedly exaggerated the importance of his place in the crisis for the dispute went far beyond his constitutional powers.

On this lesser issue and the disagreement between Herbert and Hicks-Beach, opinions were divided both in England and Australia. Sir Charles Nicholson later wrote that Bowen's actions had prevented his appointment as governor of New South Wales but Hugh Childers, Gladstone, W. Forster and Lord Dufferin expressed approval of his actions. Bowen quoted Dufferin's opinion in one of his farewell speeches;'a Governor should unflinchingly maintain the principle of ministerial responsibility. It is better he should be too tardy in relinquishing the palladium of colonial liberty than too rash in resorting to acts of personal interference'.In Victoria a petition assailing Bowen, signed by fewer than five hundred, included only eight of the thirty members of the council and five of the eighty-six in the assembly. Berry described these parliamentarians as'an extreme faction. A defeated and embittered one'. Long before this crisis Bowen had realized that Victorians were far more likely than Queenslanders to resent any interference in their'colonial liberty' by the Queen's representative.

In one of his first speeches he showed awareness of Anthony Trollope's warning of their propensity to'blow' by referring to Melbourne as'this great city, the most populous, the most wealthy and the most energetic in Australasia'. This did not prevent him from advocating Federation as the'hope of all farseeing and thoughtful Australians'. Throughout his term, both before and after 1878, he tried to respect the limits of responsible government. In spite of his close relationships with Berry, he claimed to maintain a'dignified neutrality' towards contending factions. As in Queensland he gave notice that he would be available to members of the public once a week and in addition that'persons having business which will not admit of delay will be admitted at any hour he may be in town and disengaged', and he hoped to make Government House'a neutral ground on which men of all parties can meet in harmony'.

Aided by his wife he was a social success, travelled extensively, supported all types of clubs and dispensed generous hospitality. Bowen left Victoria in February 1879.He was governor of Mauritius in 1879-82 and Hong Kong in 1882-86 and then retired from the civil service. In 1887 he chaired the royal commission on a new constitution for Malta.

His interest in colonial questions was maintained; although he took no active part in British politics, he served on the executive of the Imperial Institute. He showed continual concern in education, acting on the governing body of his old school, Charterhouse. His interest in languages and the classics had been maintained as well as his writing. In The Federation of the British Empire (London, 1886) he advocated active steps towards that goal and in selections from his dispatches, Thirty Years of Colonial Government (1889). His wife, by whom he had one son and four daughters, died on 17 November 1893.

On 17 October 1896 he married Florence, daughter of the mathematician, Dr Thomas Luby, and widow of Henry White. Bowen died at Brighton on 21 February 1899.

He had been appointed C. In 1860, and recognized by an honorary D. (Oxon, 1875) and an LL. Bowen was self-opinionated, obstinate and long-winded but such defects and his errors of judgment as in Victoria did not outweigh his abilities and his contributions as a governor.His role was particularly important in Queensland where his alliance with Herbert shaped colonial legislation and his influence ensured the operation of effective parliamentary government. This item is in the category "Collectables\Photographic Images\Photographs". The seller is "mementoes_uk" and is located in this country: GB.

This item can be shipped worldwide.- Country/Region of Manufacture: United Kingdom

- Format: Carte de Visite (CDV)

- Type: Photograph

- Antique: Yes

- Subject: Historic/Vintage

- Colour: Black & White

- Year of Production: 1868

- Singles/ Sets: Single

- Date of creation: 1870s

- Photo Type: CDV